I know this is a difficult topic for many, but there is a reason that I spent all that time establishing the conditions of asylums in the previous post. Warehousing of humans is a difficult proposition. When it comes to the most defenseless members of our society, it often becomes a state mandated hell on earth. It is rare that when conditions become such that people are unable to treated with dignity and respect, that their humanity remains intact in the minds of those charged with their care.

What this post means to address is how this comes to be. What happens in the minds of the staff? There are certainly people that are attracted to these jobs because they enjoy having people that they have total control over, and relish the ability to make them suffer, but that is not the norm, those are the exceptions. How does the norm get to the point that they simply lose their ability to see those that they are responsible for as people worthy of the same consideration that they would want for themselves?

Well, it’s a process. Many people that come to work at these facilities for a number of reasons. One, they were massive, which made them reliable employers for many people in any area that they were built. When they first open, they are clean, they are well staffed, and patient care would have had high standards.

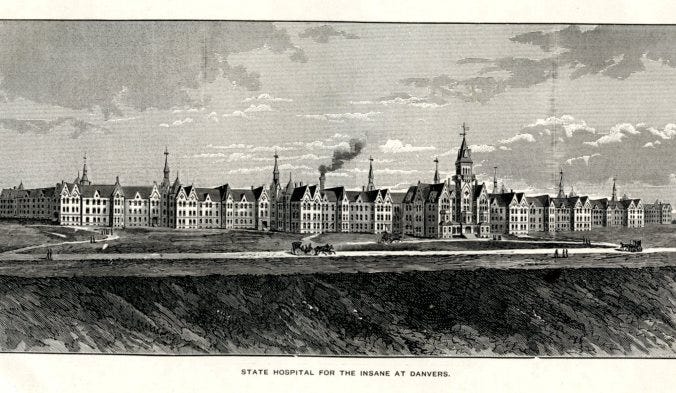

Above is Danvers State Hospital when it was first established. By the way, this is the asylum that Arkham was based on. Pretty cool little note there that I just learned as well.

On October 25, 1877, the hospital was turned over to the trustees from the state commissioners, and opened for patients May 13, 1878

It was absolutely enormous:

The Danvers State Hospital was officially opened in 1878 after four years of construction.[1] Nathaniel Jeremiah Bradlee served as the designing architect.[1]

At a cost of $1.5 million at the time, the hospital originally consisted of two main center buildings, housing the administration, with four radiating wings on each side of the Administration Block. The kitchen, laundry, chapel, and dormitories for the attendants were in a connecting building in the rear. Middleton Pond supplied the hospital its water. On each side of the main building were the wings, for male and female patients respectively. The outermost wards were reserved for the most hostile patients.

Over the years, newer buildings were constructed around the original Kirkbride, and alterations were made to the Kirkbride itself, such as a new gymnasium/auditorium on the area of the old kitchens and multiple solaria added onto the front of the wards.

Most of the buildings on campus were connected by a labyrinth of tunnels. Many of the Commonwealth institutions for the developmentally delayed and the mentally ill at the time were designed with tunnel systems, to be self-sufficient in wintertime. There was a tunnel that ran from a steam/power generating plant (which still exists to provide service to the Hogan Regional Center) located at the bottom of the hill running up to the hospital, along with tunnels that connected the male and female nurses homes, the "Gray Gables", Bonner Medical Building, machine shops, pump house, and a few others.

You would think with the size, it would be difficult to get to the point of overcrowding, but they reached capacity and began to go over in a short period of time.

The original plan was designed to house 500 patients, with attic space potentially housing 1000 more. By the late 1930s and 1940s, over 2,000 patients were being housed, and overcrowding was severe. People were even held in the basements of the Kirkbride.

Danvers is just one of many that suffered from the ideals of treatment being overwhelmed by numbers. Most of these places were not only massively overcrowded, but also had waiting lists a mile long. There was never enough space, and never enough funding. As I mentioned in the previous posts, there were massive budget cuts throughout the decades. Part of these cuts were self-inflicted by the psychiatric community, by their infatuation with things like lobotomies and the massive failure that they proved to be. The practice was heavily invested into as a cure for many different psychological and mental impairments, only to have the entire idea fall out of favor from the disastrous results it actually produced.

This left hospitals with a problem, too many people, and not being able to retain their staff. When you get to the numbers of thirty or forty, maybe even fifty patients to one staff member, you end up with a person totally overwhelmed, and that starts to wear them out mentally and emotionally. They can’t have their eyes on everyone at all times, which lead to patients being injured.

Regarding Willowbrook:

We would go there once, and we found his fingers crushed. He got them caught in a door. We come there another time, we found his leg broken. How did that happen? They don’t know. Nobody knew nothing. They were short of staff, and they had other clients to bring in. So they gave him a time limit to eat. Now, you take profoundly retarded children and you want them to eat by themselves. They don’t know how to eat. Half the stuff was on the floor. They’re eating off the floor. It was just one holy mess. And I says, oh, God, I’ve got to get this kid out of here. But, where am I going to go with him.

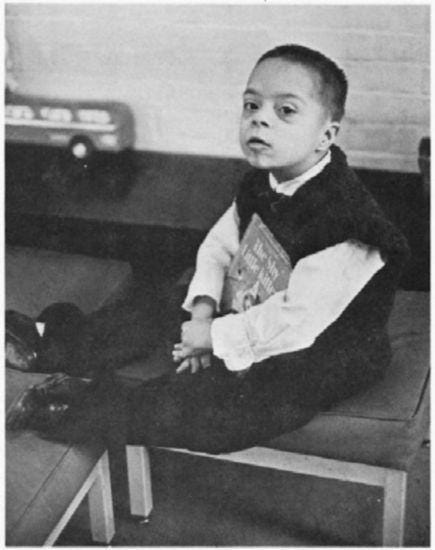

The results of children not being able to feed themselves, and not having staff on hand to help them or do it for them, was glaringly obvious:

From the testimony above, you can see that mealtimes were abject chaos, which led to another issue… getting these children clean once again. Well, frankly, that’s impossible. Unless you’re rolling out the firehouse (and yes, hosing down patients was something that happened on a frequent basis, see regarding Porirua) You aren’t getting them clean again, and you definitely can’t keep them clean three meals a day.

Regarding Porirua:

Paul Hickey was placed in Porirua at age 15. He had a brain injury after being hit by a truck, and doctors decided he needed psychiatric care - against his family’s wishes. Paul’s sister, Catherine Hickey told the commission that Paul’s treatment in Porirua was violent and dehumanising.

“When Paul first was placed in Porirua he was virtually stripped,” she says.

“They cut his long hair, which he used to hide his head injury, and took his possessions. He became so fearful he refused to shower because he couldn’t protect himself.

“Mum saw Paul with black eyes and evidence that he was regularly beaten up. He had unrelenting physical injuries. He told her that the staff would round up the patients and hose them down with cold hoses.

Or, they wouldn’t bathe them very often, at all.

Regarding Willowbrook:

I had to cut her hair because at Willowbrook they didn’t take care of my child’s hair, so it was matted. It was all stuck together, so I had to clip her hair off in order for them to keep it clean. Also, her toes and fingers was stuck together from not being oiled. And she accumulated a certain type of odor within her body. And I think that come from the neglect of not being bathed often and not being clean.

Getting hosed down with cold water would be a shock to anyone’s system, and certainly not in a good way, but when a child is already malnourished, it could overload their body’s ability to function. The fear and resistance that a patient would have to such treatment results in frustration by the staff. They don’t have time for this. They don’t have time for tantrums and refusals, they have forty other patients that has to be dealt with, and then it’s meal time all over again. Screaming, yanking, shoving, pulling, holding a patient down to just get through that moment, to get through the day, would be a common occurrence.

This then breeds resentment toward the situation. Staff weren’t paid well, they weren’t trained for their positions. The wards stank, the patients were difficult, and there would be a tremendous amount of anger at the entirety of it all. They can’t take that anger out on their bosses. Firstly, it wouldn’t work, and second, it is doubtful that their boss is in any better circumstances. Who can you take it out on? These little brats that just won’t listen!

Regarding Willowbrook:

My mom would immediately start to, upon Luis’ arrival, examine his body for marks, for signs. That was her way of finding out how Luis was being cared for. I being the oldest, was always sort of thrown in the forefront then, and expected to ask all the questions. I remember questioning a doctor one time in the state school. Here I was, this thirteen-year-old Puerto Rican kid asking this I don’t know how old white doctor about my brother and how and why he could be slapped or abused like that. Basically, the doctor looked down toward me, and told me to shut up. He told me to shut up.

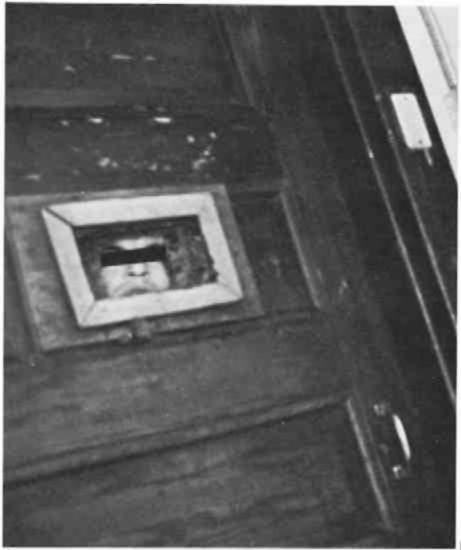

When you had to leave your child at Willowbrook, you had to not see them for six months after. This was likely explained as an adjustment period to the parents, but imagine how that was to the child left there. The feeling of uncertainty, abandonment, confusion, fear, had to be regular emotions, but to staff that was taking in another of a thousand, it would be easy to not only dismiss those emotions, but find them irritation. Deal with it, kid, this is reality now. Little by little, with every passing day, the residents become more than an inconvenience, they become the enemy, and that begins the trip down the slippery slope of evil.

The seven social processes that grease the slippery slope of evil;

Mindlessly taking the first small step.

Irritation at the patients for being patients.

Dehumanization of others.

Watching them eat, and thinking about how much they resemble animals.

De-individuation of others.

This is not a child, this is a burden

Diffusion of personal responsibility.

I change anything here. Why bother trying?

Blind obedience to authority.

I don’t care how you get it done, just do it.

Uncritical conformity to group norms.

This is just how it is.

Passive tolerance of evil through inaction, or indifference.

You deserved it, now hold still so I can clean up the blood. You shouldn’t have pissed off Paul. You know what he’s like. You get what you get. Next time, behave yourself.

It is so easy to rationalize yourself into hating people, torturing people, for being who they are, either through what you hear from others, or how those people make you feel emotionally. When the person is totally unable to defend themselves, a different process takes place in the minds of those in control, and that is that they begin to hate their weakness, and want them to suffer more. This is the same process that takes places in target child abuse cases that I spoke about in one of my early posts in this series. This is also often true in the cases of sustained animal torture.

There is a primal function in humans that despises weakness. It is usually kept under control because there aren’t outlets in the general world for it to gain traction. It is socially unacceptable to indulge it, so it is rare that people do. Those that partake are socially shunned, and often punished.

However, when the environment is tooled for this exact process to take place, it is extremely common that it will. It is almost a guarantee that you will see some of the most horrific treatment of your common man in these instances. The more beaten down they are, the greater the hatred of their weakness becomes. It is a self-fulfilling prophecy. People in asylums are already at the low end of that stick. They aren’t “normal”. They can’t take care of themselves, and often they are voiceless. They are in a prime position to be abused, and for their abusers to either not care, feel justified in their actions, or enjoy it.

There are people that don’t fall into these mentalities. There are those that hate it, but no matter what they do, how hard they work, no matter what they try to do to change it, it’s hopeless. It’s a machine that cannot be shut down so easily.

Robert F. Kennedy in 1965 regarding Willowbrook:

I visited the state institutions for the mentally retarded, and I think, particularly at Willowbrook, that we have a situation that borders on a snake pit.

It was six years after the speech by RFK that the exposé by Geraldo Rivera was done. Things had not improved in the slightest.

Geraldo’s reporting in his exposé:

It’s been more than six years since Robert Kennedy walked out of one of the wards here at Willowbrook and told newsmen of the horror that he’s seen inside. He pleaded then for an overhaul of the system that allowed retarded children to live in a snake pit. But that was way back in 1965, and somehow we’d all forgotten.

Geraldo Rivera, remembering why he got involved in the first place, what the experience did for him:

For me, Willowbrook really was a watershed in terms of emotional catharsis. It was-- you know, I was a very experienced local reporter by the time I went to Willowbrook. I had seen people dead by gunshots, and dead by fire, and dead by riot, and all the other urban mayhem. So, in that sense, I thought I had experienced the depths of the human experience. Willowbrook was so much worse than anything I had seen.

A friend of mine, Dr. Michael Wilkins, called me and said he was quitting Willowbrook because the conditions were so abysmal that he could no longer tolerate, no longer in good conscience, stay there. And that children were being abused behind the walls of the wards there. I said, that interesting, Mike, but there are laws protecting the privacy of the people in those institutions, and, they’re locked.

He said, well, the laws are preventing people from seeing a horror, and, I can get you a key. When I stepped into that ward and threw open that door with my stolen key, it was the defining moment of my life.

You know, I can’t, I can’t think of that twenty-five years later without remembering it in a way that-you know, I said at the time, a quarter of a century ago, I said, this is what it looked like, this is what it sounded like, but how can I tell you about the way it smelled? It smelled of filth. It smelled of disease. It smelled of death.

You can’t treat humans like dogs in a kennel. There is no place you can mass produce care, compassion, and concern for people. It is impossible. It is fundamentally unsound. The assembly line works for cars, it does not work for people. People need humanity. They need the spirit of compassion. They need to be loved. They need to be able to fulfill their potential, whatever their potential is. However limited, or infinite, their potential might be. They need an option. They need the opportunity to realize human potential.

Dr. Michael Wilkins in one of those people that did something. I haven’t mentioned the book, The Shame of the States, in regard to what it documented, but it was much the same. One thing that I recall distinctly from it, however, was when the reporters were trying to figure out how they would gain access to these asylums to document the conditions there, they were shocked when doctors threw the doors open for them, begging them to tell the world. To show them what was happening, to elicit help by shining a light on the situation. They didn’t have to lie to get in, they didn’t have to take a pilfered key in order to gain access, the doctors pleaded with them to bring all they had to bear. Maybe someone would listen.

That was decades before RFK’s speech, and even longer from when the documentary about Willowbrook’s condition, before the conditions became engrained, and it slid into the terminal stage of being “normal”. Things like this change people, and rarely for the better. Sure, it changes those that finally expose it for the better, but those entrenched in the daily hell of living there? It pushes them toward their darkness. That is a hard position to reverse.

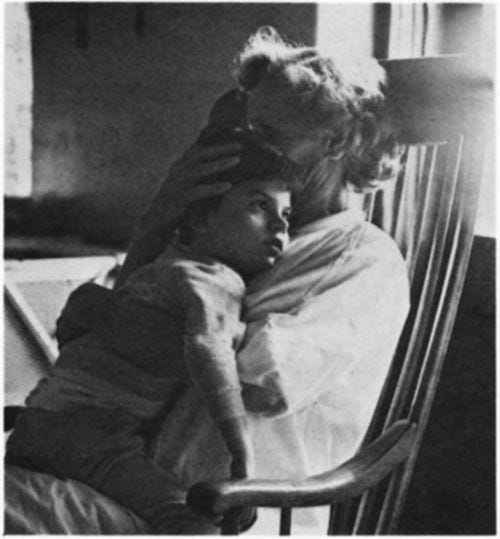

In the beginning, there was hope, reason, and a path forward that people embarked on with humanity and strength. People such as this:

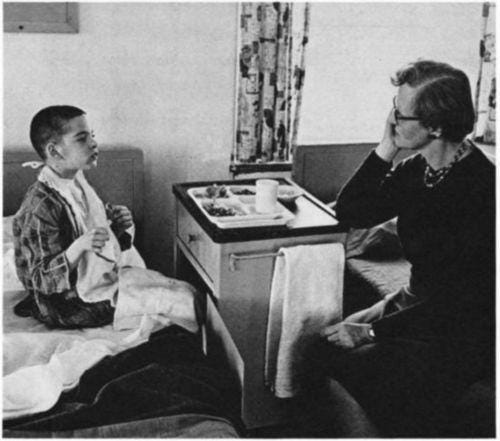

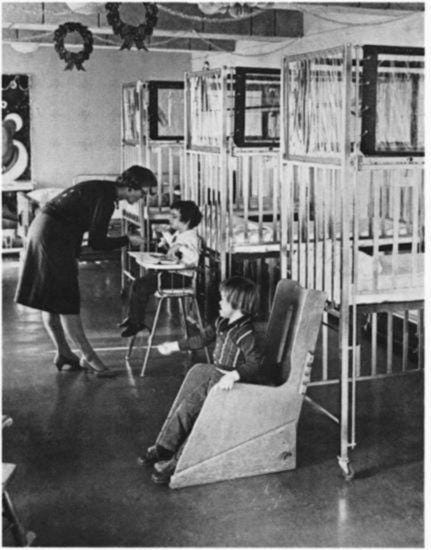

It was what created spaces like these:

However, the mentality of budget slashing, and the warehousing of patients, while looking for quick fixes instead of understanding how to meet them where they were, created the messes that destroyed a system, and many people along with it. It is a darkness that would likely never have risen in the people that it did, but for the conditions that they were places. It isn’t an excuse. All actions are choices, and many people chose to do otherwise. For those that didn’t, that is also a choice, and one that they should be held to account for. It should not, however, be ignored, that there are situations and circumstances that give way to things that don’t need to exist.

I will leave this with a brighter note, as I knnow all of this is heavy. The end of Christmas in Purgatory is a photographic essay of a facility that truly cared for their patients. You can look through it and remind yourself that just because there is darkness does not mean that all light has gone. Keep in mind when scrolling through to find them, the journey will be a hard one, and those that are immortalizedin those images are long gone. There is no helping them now. Those at the end, they were helped, but people that chose to keep them safe, warm, and cared for.

I was aware of these things and places. Whenever I see such I always wonder how they got to that point and I never see the justification as valid. I recall from when I was young that people would have family members committed and the rumor would always be that it was for the sake of convenience or frequently punish a woman who failed to live up to standards set by a father or husband.

I had a feeling that's where this series was headed - looking at the psychology of what turns the staff against the patients and how fairly ordinary people become capable of abuse.

There's alot of harsh truth in this post. Especially the bit about the human tendency to despise weakness.

It reminds me of this quote from Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi (from his book If This Is A Man):

"In fact, we are the untouchables to the civilians. They think, more or less explicitly—with all the nuances lying between contempt and commiseration—that as we have been condemned to this life of ours, reduced to our condition, we must be tainted by some mysterious, grave sin. They hear us speak in many different languages, which they do not understand and which sound to them as grotesque as animal noises; they see us reduced to ignoble slavery, without hair, without honor and without names, beaten every day, more abject every day, and they never see in our eyes a light of rebellion, or of peace, or of faith. They know us as thieves and untrustworthy, muddy, ragged and starving, and mistaking the effect for the cause, they judge us worthy of our abasement."