I am going to warn you now, there are going to be images in this post that might upset some people. If you want to tap, do so, but don’t complain if you read it, and then are upset. I did my due diligence, now do yours.

There are many of books out there that detail the mental health system in our history, and of course there is the famous news report that made Geraldo Rivera’s career when he exposed Willowbrook. If you want to see that, I would suggest this documentary:

Unforgotten: Twenty-Five Years After Willowbrook - Full Movie

That is an excellent insight into a lot of what we are going to be talking about, and yes, this is another human darkness post. As I mentioned, there are many books that speak about this sort of history, but two of the best are, Christmas in Purgatory, and The Shame of the States. Here are links to either one, if you are interested in reading them:

All right, after searching, I cannot find a copy of, The Shame of the States. I have a copy, but it is packed away at the moment, so my references to it will be by memory. I am not going on the expedition necessary to pull it out of storage at the moment. Christmas in Purgatory used to be exceptionally rare to find as well, but there is a university that started to print copies of it again, so it is more available than it was in the past. In other words, bear with me, some of this is from my ability to remember information that I took in… like fifteen years ago.

Starting now, there will be photos.

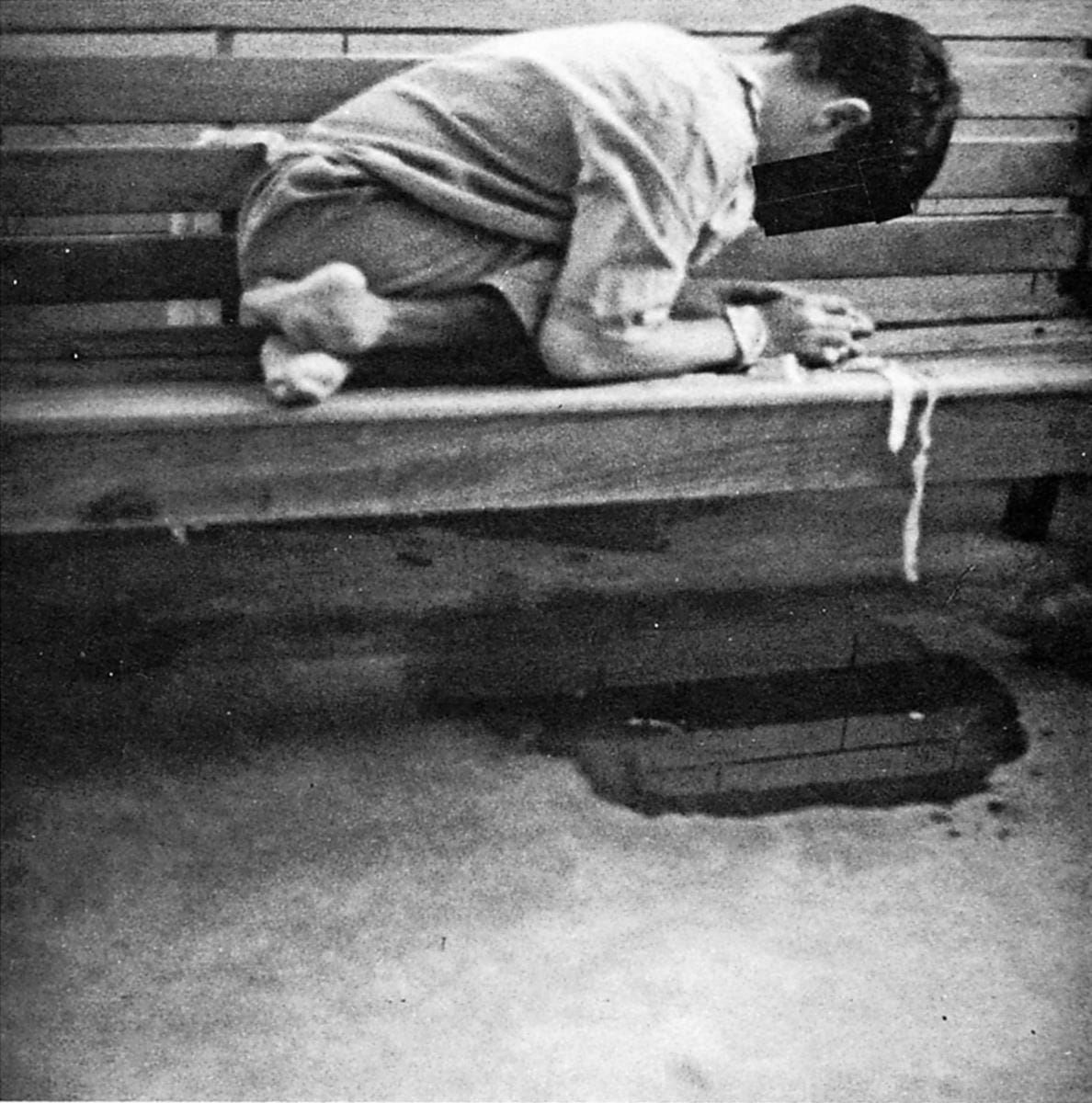

Christmas in Purgatory is a photographic essay of the mental health facilities in the sixties, much of which dealt with children. Above is simply one of many photographs taken at the time. It is a child who is intellectually delayed that has been brought to whatever facility it was taken at. As you can see, the child is very thin, likely malnourished, is alone, is on a bench with what is likely urine beneath him or her. Also, there appears to be something tied around this child’s wrists, though it doesn’t seem to be

These facilities were often so overcrowded that there was nearly no one to take care of the residents in the places, but at the same time, institutionalizing children that were considered deficient was the norm. It was encouraged by doctors, even thought the institutions themselves were vastly understaffed, they were overcrowded, often by a factor of two to three times their capacity, and the care was nearly nonexistent.

The residents of these places barely had human interaction. This isn’t because of intentional cruelty, but rather institutionalized cruelty, which is what this post is about. It is about the human darkness that can be awakened by the harsh conditions that people find themselves in. It is the infliction of the changing thought process regarding another’s humanity that these places brought about. Not always, but often enough that it is worth talking about.

You can find this sort of infliction in many places, in many situations, around the world, be it prisons, concentration camps, slavery which is still very alive and well, even in the most developed countries, and institutions for people that cannot care for themselves.

A brief aside, because I think it bears mentioning, there have been plenty of people that have had the best intentions toward those in psychiatric facilities and institutions where intellectually delayed people would be cared for. Most notably, Thomas Kirkbride. I know I have mentioned him before, though I don’t recall if that was on Quora, or here, or both.

Thomas Kirkbride designed massive asylums that were entirely designed to help people who suffered from mental illness to live in comfort and participate in their own treatment by creating a fully contained city, equipped with everything from livestock and farming, to all sorts of artistic endeavors for people to be able to engage with. These asylums were called Kirkbride Asylums, obviously named for their designer. An example of one would be the Traverse City Asylum, which you can see here:

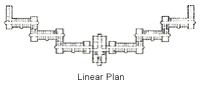

You can see the classic Kirkbride design, with the administration building being the central focus, and the wards jutting off to the side in a bat wing style, the most extremely disturbed in the furthest wards from administration.

Kirkbride genuinely wanted to design places where everything was considered to help a person find peace and sanity.

Dr. Kirkbride envisioned an asylum with a central administration building flanked by two wings comprised of tiered wards. This "linear plan" facilitated a hierarchical segregation of residents according to sex and symptoms of illness. Male patients were housed in one wing, female patients in the other. Each wing was sub-divided by ward with the more "excited" patients placed on the lower floors, farthest from the central administrative structure, and the better-behaved, more rational patients situated in the upper floors and closer to the administrative center. Ideally, this arrangement would make patients' asylum experience more comfortable and productive by isolating them from other patients with illnesses antagonistic to their own while still allowing fresh air, natural light, and views of the asylum grounds from all sides of each ward.

It was believed crucial to place patients in a more natural environment away from the pollutants and hectic energy of urban centers. Abundant fresh air and natural light not only contributed to a healthy environment, but also served to promote a more cheerful atmosphere. Extensive grounds with cultivated parks and farmland were also beneficial to the success of an asylum. Landscaped parks served to both stimulate and calm patients' minds with natural beauty (enhanced by rational order) while improving the overall aspect of the asylum. Farmland served to make the asylum more self-sufficient by providing readily available food and other farm products at a minimal cost to the state.

Patients were encouraged to help work the farms and keep the grounds, as well as participate in other chores. Such structured occupation was meant to provide a sense of purpose and responsibility which, it was believed, would help regulate the mind as well as improve physical fitness. Patients were also encouraged to take part in recreations, games, and entertainments which would also engage their minds, make their stay more pleasant, and perhaps help foster and maintain social skills.

Kirkbride’s Book, The Art of Asylum-Keeping, used to be available on the Kirkbride buildings internet archive of his works, but apparently it is no longer there. That sucks, because there is a lot of really cool information about his designs that can be gleaned from just looking at the chapter names. You can at least see that part on an archive of the site:

The Art of Asylum-Keeping chapter listing

If you click that, you should be able to see the chapter listing, including clicking on the drop-down list for the chapter collection to see the titles. Unfortunately, that is all it will do. No further information was archived. I mean… you can buy the book, but other than Christmas in Purgatory getting a new life, none of the others did, and they tend to be expensive. However, if you simply look at the chapter headings, you can see how much thought this many put into these designs.

Is this important, or am I just forcing you to learn about something that I find interesting, and you are baffled by? It’s important. To understand where things ended up, you first must understand how they started. I have done a fair amount to demonstrate to you the care and concern that went into the construction of these asylums. The people that conceptualized them did so with a desire to make things better for the patients. So, how did we get from Kirkbride’s design to Christmas in Purgatory? There are a lot of elements, and a lot of it is because of the behavior of the government that translated down all the way to the most recently hired orderly.

Kirkbride’s designs were revolutionary in idea, but they were also meant to be limited to a specific number of people. Go above the carrying capacity of the design, and it cannot hold itself together. However, while he had the best intentions, that wasn’t really the mentality of a lot of people in the past regarding the mentally ill and intellectually deficient. They were something to be ashamed of, and something to get out of the sight of “normal” society. Institutionalization was the expected thing that people did. They would be told of their children that would never function in society normally, that it was better to place them in care, where their needs were met.

It is here that I again, highly recommend the documentary about Willowbrook. You can hear the testimonies from people whose family members were placed there. Willowbrook was not a Kirkbride, as you can see, the design is wrong:

It also wasn’t built during Kirkbride’s time. It operated from 1947-1987. It was designed for four thousand residents, but it instead housed, six thousand. Just like the Kirkbride’s, once you exceed the carrying capacity, the facility cannot function normally, and there was abuse abound in its halls. The expose on it can as a great shock to many, but it wasn’t something that was unknown at the time. At least, not in the mental health community. The Shame of the States was published in 1948, and that was after years of research by its author, Albert Deutsch, a journalist and social historian. This was an ongoing problem.

In the past, if you had a child with intellectual disabilities, or if a person suffered mental illness, the pressure to put them in a care facility was pretty extreme by doctors, priests, neighbors, people in education, you name it, everyone was of the mindset, you put them away. Even further in the past, you could institutionalize someone if you were simply tired of their existence, more specifically, husbands could literally put their wife in an asylum, because he didn’t want to be married any longer, and it was more convenient than a divorce. There is a book that I have about this, but again, it’s in storage, that I cannot recall the name of, but it documents the story of a woman that was put through this. It likely is:

But, if it is, that is a reprint, because I don’t recognize the cover. It seems like it’s it, but I might be wrong. I have some obscure books, so it might be a totally different one. Anyway, the point is, getting committed, back in the day, was not too difficult. That leads to an environment that fosters overcrowding. Also, working at an asylum was not a glorious or glamorous thing to do, so understaffing was common. Also, even if the hospital was fully staffed, it would be funded for the number that the hospital should have, not what it actually had. Of course, you can now add on to this, the staff were very poorly trained. Most of the time, they have to figure it out in real time, and there wasn’t anyone there to explain to them how things should be done. All they knew was that things have to be done. No excuses.

Then, there was the issue of funding. They were always underfunded. Always. The amount of money that they had per patient, per day, was ridiculously low.

From, Christmas in Purgatory:

This book is divided into two major sections. The first section covers our visits to four institutions for the mentally retarded, located in three eastern states. The second section describes a fifth institution in another state. The latter is our way of communicating our deep conviction that many of the severe conditions with which you are about to become involved are not necessary consequences of the fact of institutionalization of mentally retarded individuals. These problems are largely the result of inadequate budgets, inferior facilities, untrained personnel, and haphazard planning— in spite of some dedicated and skilled professional workers in each of the institutions we visited. For example, the average per capita daily cost for maintaining a retarded resident in each of the four institutions we are about to describe is less than $7.00 and, in one state school, less than $5.00. In contrast, The Seaside, a regional center for the retarded sponsored by the Connecticut Department of Health, spends $12.00 daily for the care and treatment of each resident.

Christmas in Purgatory was published in 1966. $7.00 is $68.12 in today’s money, and $12.00 is $68.59. Now, currently in state hospitals, it costs about $520.00 per patient, per day. I am not arguing that state patients today are treated well, I actually know very little about that, but I do know that is a vast difference in amounts, and that vast difference was very evident in the patient care.

Another quote in Christmas in Purgatory reads:

"There is a wide range among the States in the cost per day spent for the care of the mentally retarded. Six States spent less than $2.50 a day per patient, while only seven States spent over $5.50 per day. Nationally, the average is $4.55 per day, less than one-sixth of the amounts spent for general hospital care."

The President's Panel on Mental Retardation

Regarding Willowbrook:

The moment you walked into the buildings, in specific, the building my brother was in, a strong smell of urine would hit you, a strong smell of feces. You’d hear the moaning, and the sounds of people echoing like through the hallways. Um… this is bizarre, but you wouldn’t see any of these people. They were sort of, hidden away somewhere.

And you’d walk up these long roads to patty’s building, and it was always very quiet. And then, the air would be suddenly punctuated by a scream that would just curl your hair. And, you didn’t see where it came from, and you didn’t know where it went to. The kind of moaning, and screams, and then, this tremendous quiet that would overwhelm you again. And you’d walk and you’d walk, and then finally you got to the building, and the front of the building was, I remember as being very palatial looking, almost welcoming in a sense, and you got inside, and something that always used to strike me is, as you’d walk down the path to get to the doorway, you’d look up and there was always, always, always, somebody at the window saying, “Mommy? Mommy?”, or calling for someone, and you always saw them in silhouette, and you never knew who they were. All those years, you never knew who these people were.

When you don’t have staff, it isn’t just that care is difficult. It’s impossible. In some institutions, staff had fifteen minutes to feed fifty people, alone. Not just deliver their food, feed them, from start to finish. It’s literally impossible. That is getting the most basic of needs, food, to the patient, now imagine having to bath them, get them their medication, cloth them, make sure they are safe.

Regarding Willowbrook:

Some people may vaguly recall the name, Willowbrook in connection with some kind of scandal in the early ‘70s that was exposed by the investigative reporting of Geraldo Rivera. But for those that lived there, it was a day to day struggle to survive. Life at Willowbrook held no expectations. It was endless days of emptiness with nothing to do and no one to talk to. With over 5000 residents, it was the largest institution if its kind in the world. It was called, “a school”, but fewer than twenty percent attended classes.

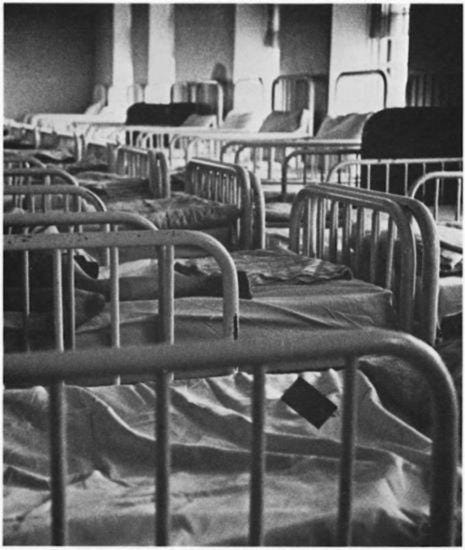

In 1969, because of cutbacks, New York State instituted a hiring freeze, and Willowbrook lostr 600 employees. Then, in 1972, the legislature cut the mental hygiene department budget to $600 million. The governor then cut it to $580 million. Willowbrook lost and additional 200 employees. The resident to staff ratio that should have been four to one, dropped to thirty or forty to one. At times, there were two or three people to take care of seventy residents, residents who shared the same toilet and contracted the same diseases. The average feeding time allocated for each individual, which should have been twenty to thirty minutes, dropped to aa horrifying two to three minutes.

Residents weren’t capable of feeding themselves a meal, simply because there was no one to show them how. Within six months of admission, most residents suffered from parasites and pneumonia. And the incidence of hepatitis was 100%. Emotional trauma from being left together unattended was widespread.

The overcrowding can be seen in a photo of one of wards:

Side note. I sent out a post asking if you guys wanted one or two posts about this, but pretty much immediately after it went out I reached the email length limit, so two posts it is.

I have no idea how this should be fixed. Mental illness seems to always bring out the dark side of human nature as after all the abuses were exposed the reaction was to "mainstream" the mentally ill with the results being widespread homelessness. The small town I went to school in has begun a crackdown in panhandlers and the homeless with the apparent intention of just driving them away and the elected officials seem to be pleased with themselves

I feel like the pendulum has swung too far the other way these days but somehow the same issues remain. Mental illness is not taboo or shameful anymore, these days a lot of people even want to have it for attention. But illnesses are still being misdiagnosed and medications are being overprescribed. Psych wards are full of people who should not be there (often put there by relatives who just can't be bothered). By trying to fix something that wasn't there in the first place, people are digging themselves holes that they will have a hard time crawling out of. Babes, you don't need Zoloft. You just need to leave your room, get some sun, exercise and hang out with your friends and family. Leave the psychiatric facilities for the people who actually need it.